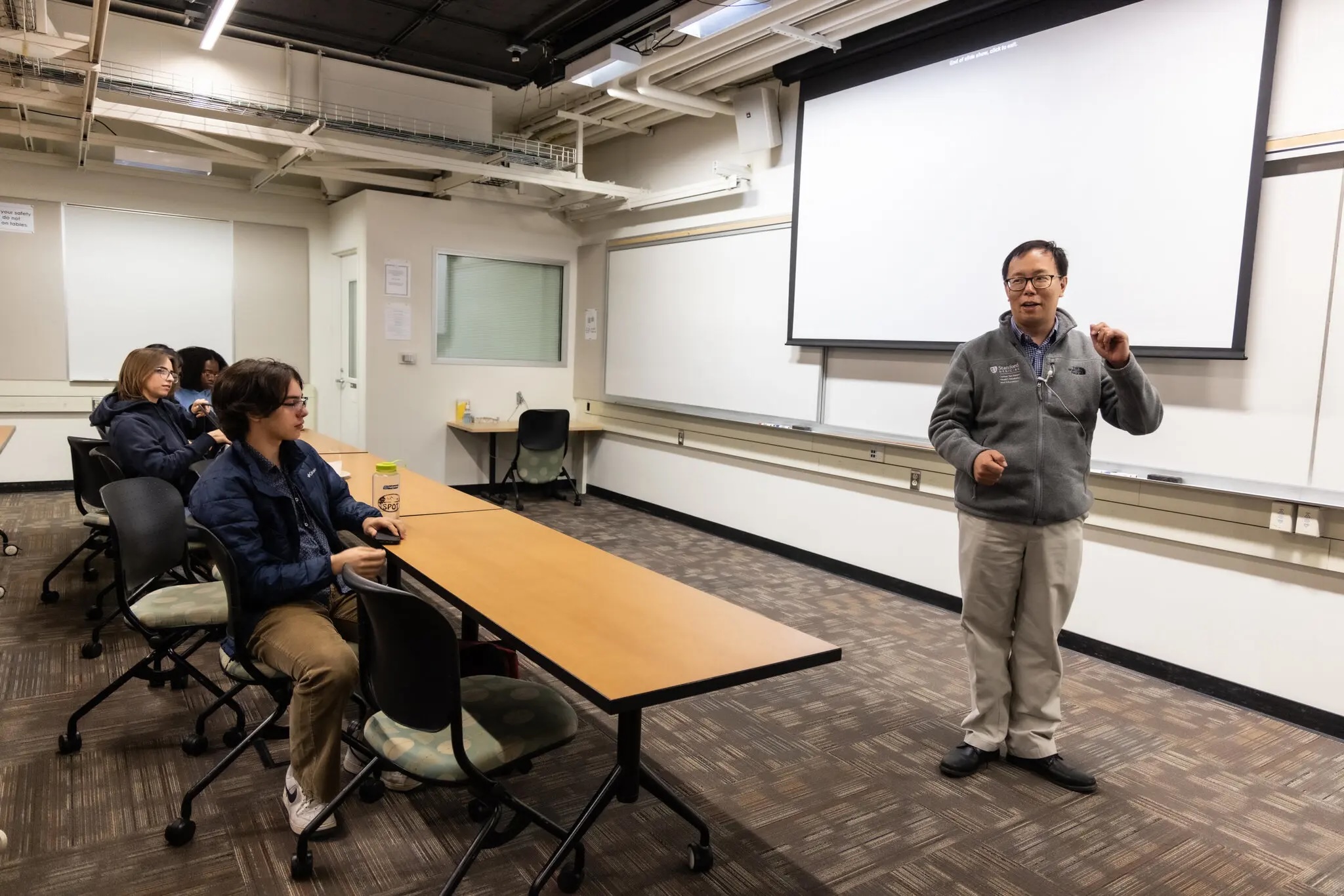

Dr. Bryant Lin stood before his class at Stanford in September, likely

one of the last he would ever teach.

Just 50 years old and a nonsmoker, he had been diagnosed with Stage 4

lung cancer four months earlier. The illness is terminal, and Dr. Lin

estimated that he had roughly two years left before the drug he was

taking stopped working. Instead of pulling back from work, he chose to

spend the fall quarter teaching a course about his own illness.

Registration for the class had filled up almost immediately. Now the

room was overflowing, with some students forced to sit on the floor and

others turned away entirely.

“It's quite an honor for me, honestly,” Dr. Lin said, his voice

catching. “The fact that you would want to sign up for my class.”

He told his students he wanted to begin with a story that explained why

he chose to pursue medicine. He picked up a letter he had received years

earlier from a patient dying of chronic kidney disease. The man and his

family had made the decision to withdraw from dialysis, knowing he would

soon die.

Dr. Lin adjusted his glasses and read, choking up again. “'I wanted to

thank you so much for taking such good care of me in my old age,’” he

read, quoting his patient. “'You treated me as you would treat your own

father.’”

Dr. Lin said this final act of gratitude had left a lasting impact on

him. He explained that he had created this 10-week medical school course

— “From Diagnosis to Dialogue: A Doctor's Real-Time Battle With Cancer”

— with similar intentions.

“This class is part of my letter, part of what I'm doing to give back to

my community as I go through this,” he said. Later, an 18-year-old

freshman in his first week at Stanford caught up on a recording of the

class, which was also open to students outside the medical school. The

course had filled up before he could enroll, but after emailing Dr. Lin,

he received permission to follow along online. He had questions that

needed answers.

Last spring, Dr. Lin developed a persistent and increasingly severe

cough. A CT scan showed a large mass in his lungs, and a bronchoscopy

confirmed the diagnosis: cancer. It had metastasized to his liver, his

bones and his brain, which alone had 50 cancerous growths. He is

married, with two teenage sons.

The diagnosis was particularly cruel given his work. Dr. Lin, a clinical

professor and primary care physician, was a founder of the Stanford

Center for Asian Health Research and Education. One of its priorities

has been nonsmoker lung cancer, a disease that disproportionately

affects Asian populations.

A self-described “jolly” person, Dr. Lin is known for his booming laugh

and voice made for radio. A longtime mentor called him a “pied piper”

for ideas — someone who can rally people around a vision. In addition to

his other work, he directs the medical humanities program at Stanford

and has patented medical devices.

Across his roles, he stresses that people are at the heart of medical

practice. He said he tries to emulate an “old-timey country doctor” and

once helped throw a 100th birthday party for one of his patients.

Dr. Lin learned that his cancer was advancing rapidly. He felt pain in

his spine and ribs, and his weight dropped. His doctor put him on a

targeted therapy designed to attack the specific mutation driving his

cancer. He also underwent chemotherapy, which caused nausea and sores in

his mouth.

“Day in the life of a cancer patient,” he said in a video diary he began

keeping after his diagnosis. “So I guess that's what I've become. Rather

than a dad or husband.”

After a few cycles of chemotherapy, his breathing and coughing began to

improve, and scans showed drastic reductions in the cancer's extent. He

continued to see patients and teach, and he began to think about what to

do with the time he had left.

The dying dialysis patient had written a letter because he wanted Dr.

Lin to know he was appreciated. Dr. Lin had a couple of ambitions for

his own message to his students. He liked to think that some of them,

having taken his course, might go on to dedicate themselves to some

aspect of cancer care. And he wanted them all to understand the humanity

at the core of medicine.

Dr. Lin's class met for about an hour each Wednesday. One week, he led a

session on having difficult conversations, where he stressed that

doctors should be honest enough to say “I don't know” when necessary —

an answer he had to accept as a patient amid the uncertainties of his

own diagnosis.

In another class, he discussed how spirituality and religion help some

patients cope with cancer. Though he isn't religious, he shared that he

found comfort in others' offering to pray, chant or light a candle on

his behalf.

And in a session on the psychological impact of cancer, Dr. Lin spoke

about the disappointment he felt after a scan showed that some of his

tumors had shrunk but hadn't disappeared — because, deep down, he was

still holding out hope for a miracle.

He taught the sessions using what he described as the “primary care”

model. He was the initial point of contact, sharing how his cancer

diagnosis had affected him, but he referred his students to specialists

— guest speakers — when more exploration was needed.

One of his first guests was Dr. Natalie Lui, a thoracic surgeon and lung

cancer expert. Standing before a set of slides, she placed Dr. Lin's

diagnosis within the broader context of lung cancer among nonsmokers,

particularly in Asian populations.

“In the U.S., about 20 percent of people diagnosed with lung cancer

never smoked,” she said. “But in Asian populations and Asian American

populations, that could be really up to 80 percent in some racial and

ethnic groups,” she added, with Chinese women especially likely to

receive the diagnosis.

For a class on caregiving, Dr. Lin brought in Christine Chan, whom he

introduced as “my wonderful wife.” The students, some in scrubs, had

been chatting and laughing, but grew quiet as the session began. Chairs

shifted closer, and one person stood to get a better view. Like her

husband, Ms. Chan softened difficult truths with a smile, meeting

students' eyes across the audience. She spoke to the students as though

they were or would become caregivers themselves.

Ms. Chan said she had been overwhelmed at first, buried in medical

terminology she didn't understand. Wanting to give her husband the best

chance at continued health, she tried cutting out sausages and red meat

from his diet — but felt disappointed when he turned down some of the

new foods she made. While she encouraged caregivers to lean on friends

and family, she warned that coordinating well-meaning offers of help

could become a task in itself. An M.I.T. graduate and program manager at

Google DeepMind, she acknowledged that letting go of her instinct to

plan for the future had been difficult.

“We just have to go through it one day at a time,” she said. Dr. Lin

nodded in agreement.

Watching Dr.Lin teach, I often wondered what his students, many in their

late teens and early 20s, were thinking. What was it like for them to

become attached to him as a professor, knowing his prognosis was so

dire?

When I asked, some used the phrase “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to

describe the course. Others saw Dr. Lin as brave and said that if they

were in his position, they probably wouldn't be teaching a class.

But a significant number of students said they were confused. They had

signed up for the course expecting something more “existential,” as one

student put it. They were prepared for a harrowing emotional experience.

But, save for choking up during the first lecture, Dr. Lin remained

steadfastly upbeat, even cracking jokes.

When his wife told the class about cleaning up his diet, he feigned

alarm, saying, “I'm like, 'I don't eat this food!’” And when he quizzed

his oncologist, another guest speaker, about what might come next for

people who developed resistance to the drug he was taking, Dr. Lin

quipped, “Asking for a friend!”

It was difficult for some students to reconcile this upbeat attitude

with the severity of his diagnosis. Gideon Witchel, of Austin, Texas,

was one. He was the 18-year-old freshman who had watched a recording of

the first class from his dorm room. A spot had since opened up, and now

he was enrolled.

When Mr. Witchel was 5 years old and his sister was 3, his mother,

Danielle Witchel, was diagnosed with breast cancer, but he had never

talked to her about it in depth. He had never been able to say, “Tell me

the story of your cancer.” He was taking Dr. Lin's class in hopes that

it would help him start that conversation.

One of his strongest memories of his mother's illness was of playing

with her colorful scarves while she sat on the couch, bald. But looking

back, he felt unsettled. The thought that she could have died was

terrifying.

During the session on spirituality, the idea of control came up, and

that gave Mr. Witchel the opening he needed to approach Dr. Lin. He

lingered after class and asked the professor whether he had chosen to

teach the class to regain a sense of control over his diagnosis. Dr. Lin

replied without hesitation: no. He said he tried not to dwell on what

was out of his control. “I'm very conscious that I have limited time

left,” he said. “So I think about that. How am I going to live my life

today? Is this a worthwhile way to spend my time?”

The class, he said, was worthwhile. “Does that make sense?” “It's

powerful,” Mr. Witchel said. “It's impressive that you're doing

this.”

“You know, I think if I were 20, it would be different,” Dr. Lin

responded. He said his work as a doctor had perhaps enabled him to cope

faster than other people would. He asked again, “Does that make

sense?”

Mr. Witchel nodded, and Dr. Lin smiled, this time with a shrug.

Sometimes, in private, Dr. Lin was less sanguine than he appeared in

class. More than once, he told me, he looked back on time passing and

thought, “Wow, that was a fast week.”

When he saw an older person, he was reminded that he probably wouldn't

live to be that age. What hurt was missing not the opportunity to grow

old, but what growing older represented — the chance to attend his

children's graduations, to watch them grow up and start their own

families. The expectation of spending his later years with his wife.

Dr. Lin and Ms. Chan had told their children about his diagnosis, but

they weren't sure the boys fully understood what it meant. It was hard

to think of a man as dying when he looked as healthy as Dr. Lin did.

“They think, Daddy can take care of everything, fix everything, solve

everything,” Dr. Lin said.

He referred to the class as his letter to his students, but he had

crafted an actual letter to his sons for them to read after he was

gone.

“Whether I'm here or not, what I want you to know is that I love you,”

he wrote. “Of the many things I've done that have given my life meaning,

being your daddy is the greatest of all.”

For the last class, held on a sunny day in December, Dr. Lin and his

students met in a library at Stanford Hospital. The room was walled in

with glass, offering a view of the foothills and flowering plants on the

adjoining rooftop garden. Students spilled over from the designated

seats into a computer cluster, and the librarian leaned against one of

the sections of shelves to watch.

Near the end of the class, Dr. Lin stood at the front of the room,

folding and unfolding a piece of paper where he had printed his closing

remarks. It was time to finish his letter.

He gave what he called his version of Lou Gehrig's farewell speech,

referring to the Hall of Fame baseball player for the New York Yankees

who died at 37 from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or A.L.S., an

incurable neurological disease.

Dr. Lin unfolded the paper once more, this time all the way. “For the

past quarter, you've been hearing about the bad break I got,” he said,

echoing parts of Gehrig's address at Yankee Stadium. “Yet today, I

consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.”

With that, he choked up. “Sure, I'm lucky,” he said. He said he was

lucky to have his two sons, who brought joy and laughter into his house.

His teaching assistants, who made the course possible. The Stanford

community, his colleagues and the people at the Asian health center. His

students and residents. His patients. His friends. His parents. His

wife.

“So I close in saying that I may have had a tough break, but I have an

awful lot to live for,” he said. “Thank you. And it's been an honor.”